Haitian Flag Day celebrates the creation of the Haitian Flag representing the unity of Haitian African and Creole forces in Haiti in 1803.

The message for everyone, Haitian or not, is that together we are strong.

Haitian Flag Day

Haitian Flag Day is celebrated on May 18 in Haiti and across the Haitian diaspora, including in New York City. It commemorates the creation of the Haitian flag on May 18, 1803.

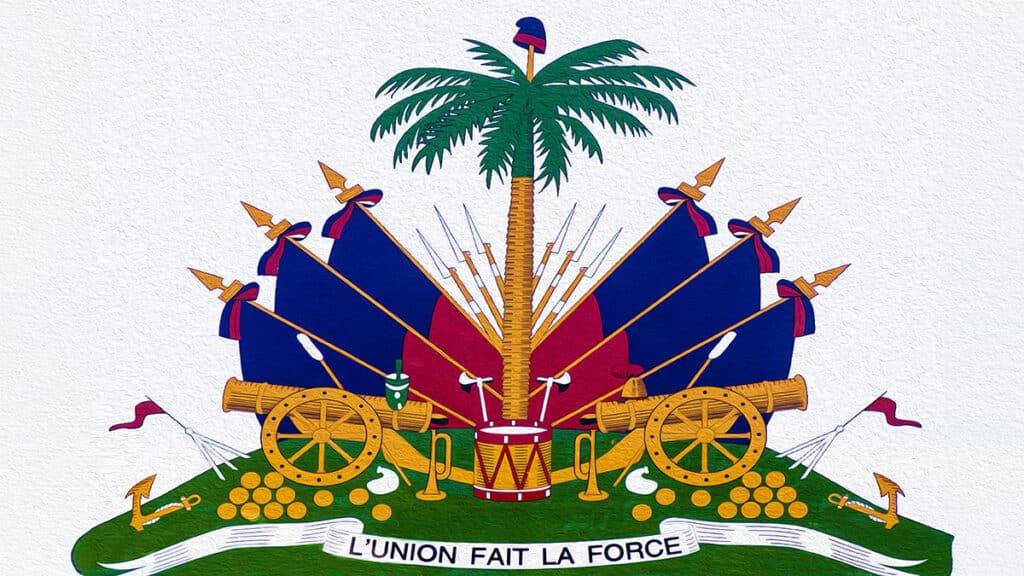

The Haitian motto is “L’Union Fait La Force” which means “unity is strength.” That rings true in African American communities too. To be successful, we have to rely on each other.

In the United States, Haitian Flag Day celebrations are also a celebration of Haitian contributions to the society and culture of the United States.

A Brief Story of Haiti

The story of Haiti is important to who we are as Americans in the United States and across the Americas today, but is not well told just because of racism. [We can’t say this story is entirely correct, but it is our best understanding at the moment.]

The French sugar colony of Saint-Domingue (1659-1804) was the richest French colony and the richest colony in the Caribbean. It must have once been a beautiful place, but the colony enriched France through the most brutal, inhuman kind of industrial slavery which destroyed both the people and the land. African peoples were worked to death and anyone who resisted was subjected to the most inhuman, medieval torture.

Saint-Domingue society became separated into three groups: French colonizers, French-African “Creole” children of the colonizers (“free coloreds”), and African slaves. Being American-born, Creoles were automatically second-class, but they were a sophisticated, highly-educated community, often educated at the best schools in Europe. The sophistication of jazz comes from Creole peoples in New Orleans.

Though well-educated, the Creole community was used by the French colonizers to control the African slave community. The African slave community in Saint-Domingue was mostly Yoruba, a people of Nigeria, Benin and Togo who are known in Africa for their diplomatic skills.

[After living in the Dominican Republic, 100 miles from Haiti, I realize that a lot of Haitian culture is actually based on old Kongo culture of Central Africa.]

The Yoruba kingdom grew under its fourth King Changó, but entered a period of instability after his death. [In the same way that Catholic saints are venerated, Changó was a historical person. Like the Greek god Zeus, thunder and lightning are signs of Changó’s energy.] The kingdom had declined enough by the 18th century that Yoruba enemies captured and sold them into slavery. That’s how the Yoruba arrived in the Caribbean.

The Yoruba religion (called Santería by the Spanish) became the dominant religion among Africans in the Caribbean and South America. Vodou in Haiti, Voodoo in New Orleans, Lucumí or Regla de Ocha in Cuba, Candomblé in Brazil and other African-American religions are derived from the Yoruba religion.

Even U.S. blues legends about meeting the “devil” at the crossroads are a reference to Yoruba religion. The orisha of the crossroads is Eleguá. [There’s no devil here. The Yoruba religion encourages the achievement of one’s human potential. Slavers demonized everything African as a means of control.]

During roughly the 1700s, the rise of the scientific and humanistic ideals of the Enlightenment in Europe began breaking down the authority of pope and king. [Blind loyalty to patriarchy is the great weakness of Latin culture.]

The transition from medieval monarchies of popes and kings towards modern ideas of democracy and individual responsibility is a process that continues in fits and starts today, even in the United States. It’s the proverbial two steps forward, one step back.

In 1776, the U.S. Declaration of Independence was more than just something for future generations to commemorate with firework displays. It was a great humanist document that inspired the adoption of Enlightenment ideals in Europe. It’s wasn’t perfect. It didn’t end human slavery.

In 1789-1799, the French Revolution ended the monarchy in France and began promoting the idea of liberty, brotherhood and equality (or death).

Saint-Domingue’s Creoles took these ideals seriously and believed that liberty, brotherhood and equality would apply to them too. The French revolutionary government even granted citizenship to “free coloreds,” but French landowners in Saint-Domingue refused to allow it.

On August 21, 1791, as a hurricane moved in with thunder and lightning (hurricanes are a sacred power in the Caribbean and thunder and lightning are signs of Changó or his female aspect Santa Barbara), an African slave revolt was launched at a secret Vodou ceremony.

Like all revolutions, the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) was a messy affair. At the time, the French Army was one of the most powerful armies in the world, like the U.S. Marines are today.

As the only nation in history founded from a slave revolt, the founding of Haiti in 1804 is a great human accomplishment. What made it succeed was the combination of African (former slave) and Creole (French-African “free coloreds”) forces.

The Story of the Haitian Flag

From May 14-18, 1803, anti-French forces met at the Congress of Arcahaie, a coastal town in what is now Haiti. Former slave, Jean Jacques Dessalines was the main leader of the Africans. Alexandre Sabès (Pétion) was the main leader of the Creoles. Seeking strength through unity, they joined forces.

On May 18, 1803, Dessalines tore the white section out of a French flag. His goddaughter sewed the pieces together to create the Haitian flag. Blue represents the African peoples. Red represents the Creole peoples. The Haitian flag represents their union.

There is a lesson here for us in the United States today. Our Black and Latin communities should get it together.