Hélio Oiticica is one of the big three Brazilian contemporary artists along with Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape. Each in their own way, sought to take art away from the temples of the elite and place it in the social context of the people.

When governments fail, common people band together to salvage civilization. The sad legacy of Portuguese and Spanish colonialism is that Latin American governments fail often. Even today the governments in Brazil, Venezuela, and the United States are failing.

Brazilian artists understood this both consciously and subconsciously. They were not just looking for new ways to make art. They were looking for new social models that are inclusive. In a way, they are Brazilian patriots.

While the art world was focused on Abstract Expressionism and then Pop Art in New York; Oiticica, Clark, Pape and other Brazilians were making some great art.

They quickly moved into installations, multimedia, performance and conceptual art, perhaps even before the more mainstream artists who are credited as founders of those movements. Though he died young (at age 40) Hélio Oititica was in the thick of it.

Hélio Oiticica is one of the roots of Tropicália

Hélio Oiticica was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on July 26, 1937. He was active from the mid-1950s until his death in Rio in 1980.

After native art, Baroque was the first major influence on Brazilian art. The exaggerated grandeur of Baroque came with the colonial Catholic church.

Looking to shed the legacies of colonialism, post-war Brazilian artists sought a different muse. They found it in Concrete Art abstractions that avoid representations of the natural world.

In the mid-1950s Oiticica got involved with Grupo Frente which gave Latin flavor to the geometries and primary colors of Russian Suprematism.

Abstraction was useful because it avoided being used for state propaganda like the work of the Mexican muralists, and by avoiding the cliches of representation, it kept the authorities off your back.

In 1959 Oiticica became part of the Neo-Concrete Movement. This is where he ran with Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape. Here they made the switch from art for art’s sake to art for the viewer’s sake. We don’t want to make art for museums, we want to live an artistic life. We don’t make art for the elites, we make art with and for the people. We make art not to just look at in museums and books, but to be experienced. We live art.

Oiticica’s most famous work is the installation Tropicália. It gave a name to the Brazilian version of the youth energy that burst out around the world in 1967. Tropicália became a Brazilian artistic movement in theatre, poetry, and music. The album Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis (1968) was Caetano Veloso and Gilbert Gil’s musical manifesto of this force.

This was the time of the Latin American dictatorships. Open critique could lead to jail, torture, and death. Even though they didn’t want to challenge the government directly, artists were speaking out. They just spoke in code. Their words might not translate into a direct threat to the dictatorship, but everyone understood what they meant.

Artists weren’t only trying to get people to engage with their art, they wanted people to engage with the society at large. Brazil has a huge problem with this. Even today, the majority of Brazilians live outside the formal social structures.

Interestingly, this brought us back to the Baroque. Instead of the exaggerated grandeur of a Baroque paintbrush, Oiticica created a Baroque sensibility through the endless variety of the people’s experience of his art.

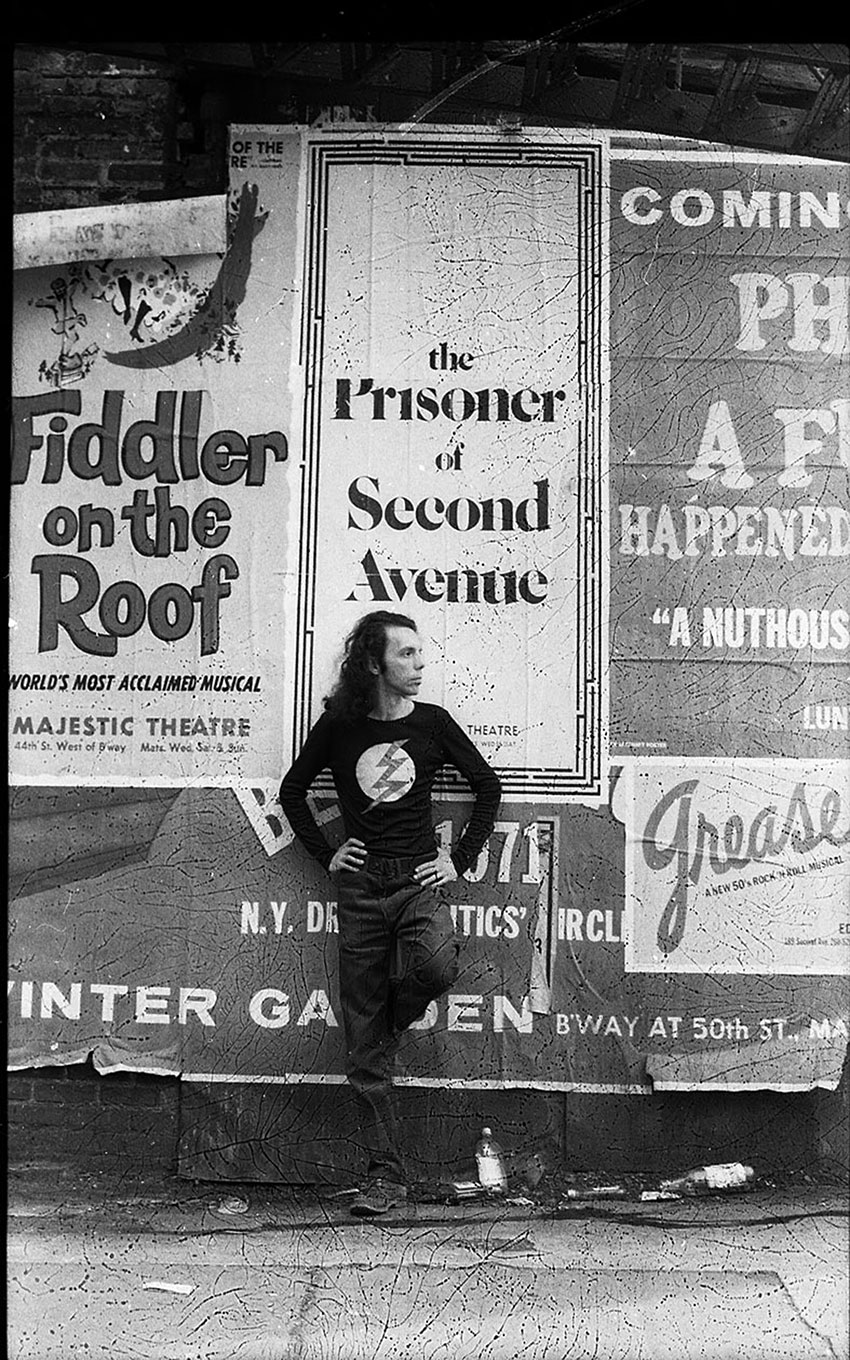

Hélio Oiticica in New York City

Hélio spent time in New York City in the 1970s just before he returned to Rio de Janeiro and passed away in 1980.

Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium at the Whitney Museum from July 14 – October 1, 2017 is the first major U.S. retrospective of Oiticica’s work in two decades.

Oiticica was not particularly into preservation of his art, and much of what existed was destroyed in storage. Collectors were not very active at the time because Brazil was far away and most didn’t think we were capable of great art.

But Hélio Oiticica had a lot to say then, and he has a lot to say to us now at this most bizarre moment in American history.