Babalú-Ayé is a West African, Central African and African Diaspora orisha of contagious diseases and epidemics, but also healing from them. As the orisha of both sickness and healing, he is both feared and loved.

In New York, we mostly know the saints through Caribbean traditions, especially Yoruba (parts of Nigeria/Benin/Togo) traditions in Cuba. Actually there are many related faiths in West Africa, Central Africa and the African diaspora, just as there are many distinct, but related, variants of Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

In the Americas, African Diaspora traditions are syncretized (blended) with Christianity. There is no conflict between the two. You can be 100% Christian and 100% Yoruba. No problem. In fact, in Cuba, Christianity survived the Revolution in the African Diaspora religions.

Signs of Babalú-Ayé

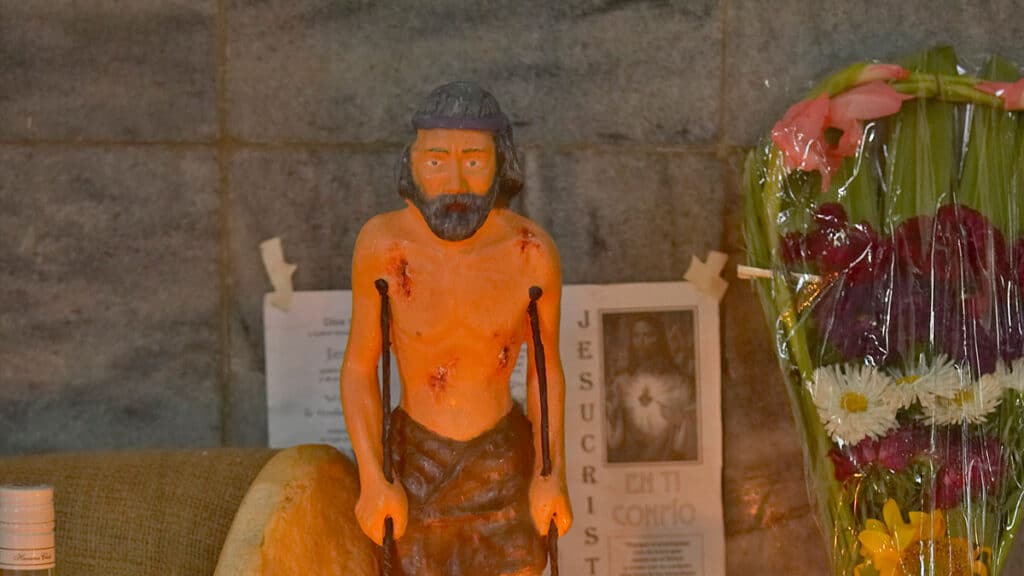

Babalú-Ayé is often covered to hide his diseased skin. In some traditions he is covered because being healed, he is so handsome that he cannot be seen.

He uses a ritual broom for purification, earthen vessels, and cowry shells. The faithful offer him grain.

His number is 17 which is a prime number.

It’s interesting how the god of the earth, and of sickness and health is worshiped at this time. In the northern hemisphere, the Earth sickens through fall, dies in winter, and returns to health in spring and summer. The Earth is brought back to life like Lazarus in the bible story.

Babalú is also associated with movement. In the north, we are entering the slowest time in the cycle of life, but are about to get moving again.

There are parallels between spirituality, the natural cycles of Mother Earth, and the psychological journey of life.

Saint Lazarus

Under Catholic repression during the time of human enslavement, Africans preserved their faith by syncretizing (blending) their own traditions with the slavers’ Catholic traditions. In Cuba, it is perfectly normal to practice both Catholic and African traditions.

In the Americas, Babalú-Ayé is syncretized with the Catholic Saint Lazarus. There are actually two Saints Lazarus: Saint Lazarus of Bethany (John 11:18, 30, 32, 38) and the beggar Lazarus (Luke 16).

Saint Lazarus of Bethany was raised from the dead by Jesus after he had been entombed for four days. In popular culture, Saint Lazarus has become a metaphor for the restoration of life.

The beggar Lazarus is a character in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus. In this story a poor beggar lived on the street outside a rich man’s house. Both died around the same time. Finding himself in hell, the rich man asked Father Abraham to send the beggar Lazarus to help him. Abraham declined saying that the afterlife balances out life. We happen to disagree with this interpretation because Colonizers and cons use the fantasy of a better next life, to get people to accept horrible circumstances in this life.

Diaspora veneration of Babalú-Ayé conflates the two Lazarus characters.

La Caminata at the Church of Saint Lazarus in Rincón, Cuba

“La Caminata” is a famous Cuban pilgrimage to the Church of Saint Lazarus in Rincón, Cuba on December 17 every year.

People walk to the church. Some crawl. Some push little carts with a statue of Saint Lazarus dressed in burlap and wearing a red cloth. The devoted make themselves bloody and dusty crawling as they meditate on the harsh character of life.

In Caribbean Indigenous tradition, people blow cigar smoke at images of the saint. In total, this is a rich representation of the Indigenous + European + African traditions.

The pilgrimage may be done in hope that a prayer will be answered or to give thanks for a prayer delivered. All cultures do similar things.

Awán

In the awán ceremony for Babalú-Ayé, an empty basket is circled with plates of food. Practitioners cleanse themselves with handfuls of food which they throw into the basket. There are many local variations of this.

Ricky Ricardo’s Signature Song

For those old enough to remember the Ricky Ricardo character played by Cuban actor Desi Arnaz in the U.S. television show “I Love Lucy,” Ricky’s signature song was Babalú, a Cuban song about Babalú-Ayé.

The 2020 Letter of the Year

Every December 31st, orisha faith organizations in Cuba tell the fortune of the coming year. It’s called the Letter of the Year. The West African tradition follows the yam harvest in June. In the Caribbean, this African New Year’s celebration is syncretized (blended) with the colonizer’s European New Year tradition.

The 2020 Letter of the Year foretold a year of terrible sickness. It was the year when Covid-19 struck the world. The Letter of the Year was right and Babalú-Ayé is the orisha to whom we pray for deliverance.

Death is the Only Certainty in Life

The cliché is true. We all have to face our own death.

In some Caribbean Yoruba traditions, an interesting group of saints helps us through the process of dying.

- The sick turn to Babalú-Ayé for comfort and help.

- When we die, Babalú introduces us to his friend Yewá, the saint of the cemetery. She dances on graves, but don’t be scared. Yewá is helping the dead through their transition. [Editor Keith: I love to dance and my last dance will be with Yewá.]

- When ready, Yewá introduces us to Oyá, the orisha of wind, storms, and death; but also of rebirth. Interestingly, African Diaspora Oyá is a lot like the Supreme Taíno God Atabey, who brings wind, storms, death and life.

It’s very interesting that African and Caribbean traditions are so similar, and that was before contact. Humans do similar things around the world and across time, because we share a human nervous system.

¡Maferefún Babalú-Ayé!