Lourdes Lopez is the Artistic Director of the Miami City Ballet, one of America’s great ballet companies.

Lopez was born in Cuba, raised in Miami and grew up in the School of American Ballet here in New York City.

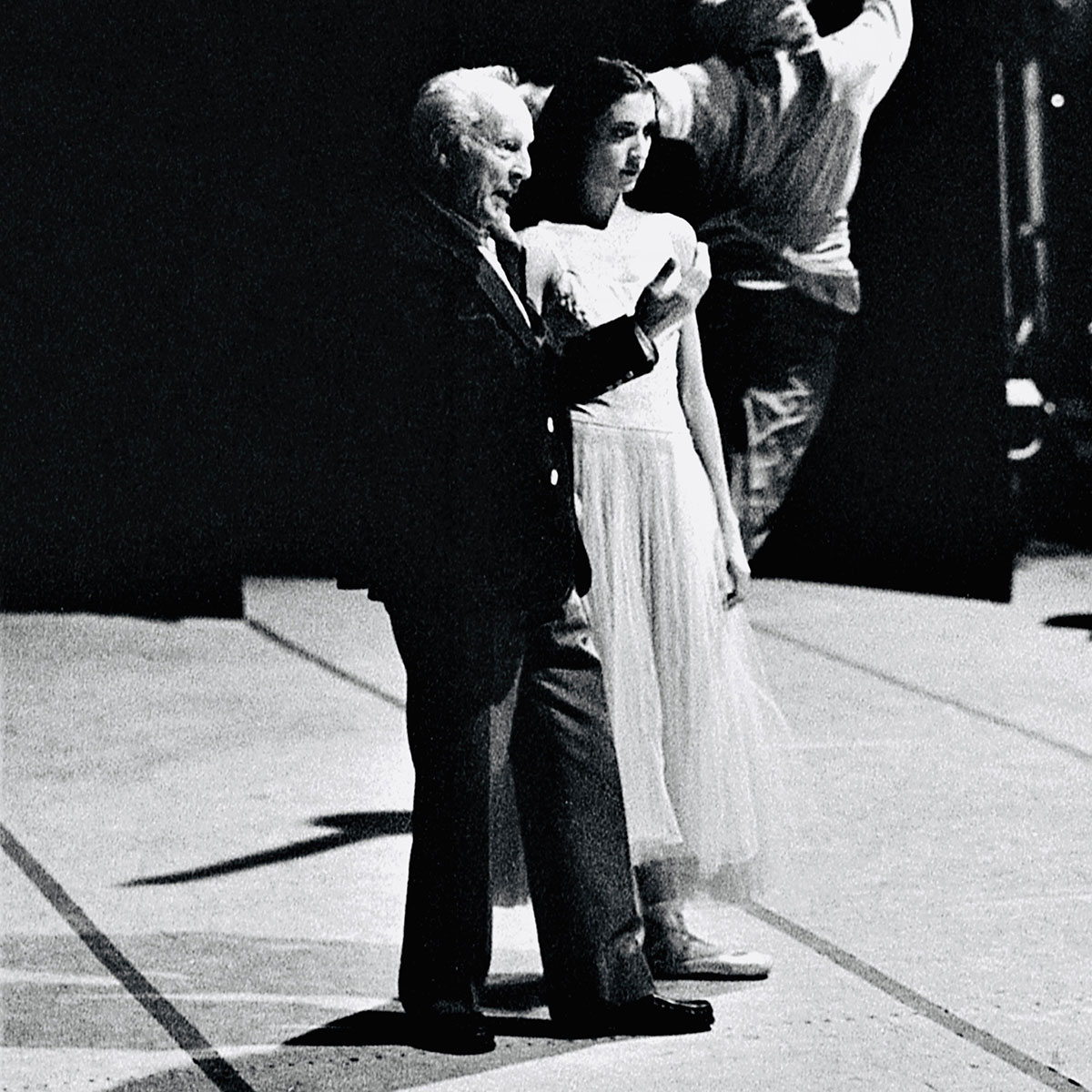

A determined and natural talent, she became a New York City Ballet Principal who danced for both City Ballet founding choreographers George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins.

[An early version of this article mistakenly named Lourdes as a Soloist. In fact, she is New York City Ballet’s first Latina Principal dancer. Our apologies.]

After dancing, Lopez was chosen to be the founding Executive Director of The George Balanchine Foundation, co-founded the Cuban Artists Fund, and co-founded, with Christopher Wheeldon, the Morphoses contemporary ballet company.

Lopez is the only Latina to lead one of America’s major ballet companies. She is also the only artist on the Ford Foundation’s Board of Trustees.

Lopez was recently named one of “The Most Influential People in Dance Today” by Dance Magazine. She is an honoree at the 2018 Dance Magazine Awards to be held at the Alvin Ailey Citigroup Theater in Hell’s Kitchen, Manhattan on Monday, December 3, 2018.

Suki Schorer, School of American Ballet

We asked Suki Schorer, former New York City Ballet Principal and Permanent Faculty member at the School of American Ballet, what she saw in the young Lourdes.

“When Lourdes was around 16 I could see the dancer she would become. She had talent and was extremely focused. She was musical and well coordinated: a natural performer.

She was in the lecture demonstration program that I ran from 1972 until the 90’s. She performed around 1973 or 1974 in this group and was always ready for the show with enthusiasm and a bright smile.

Lourdes replaced an injured dancer in my first SAB workshop to dance the lead in the first movement of “Stars and Stripes.” She brought down the house with her high kicks, brilliant turns, jumps and joyous expression. She joined the company and the rest is history. Lourdes is a beautiful dancer with a thoughtful mind.”

Jennifer Stahl, Editor-in-Chief of Dance Magazine

We asked Jennifer Stahl, Editor-in-Chief of Dance Magazine, why the magazine chose to honor Lourdes this year.

“The selection committee chose Lourdes because she has shown herself to be an exceptional leader at Miami City Ballet. She is one of the very few woman artistic directors at a major ballet company. Lourdes has shown the ability to bring out the best in her dancers and is also widely respected by them, which is pretty inspirational.”

Brian Seibert, New York Times Dance Critic

About Miami City Ballet’s performance at the Balanchine Festival at New York City Center, New York Times dance critic Brian Seibert wrote, “Miami City Ballet proved that it belongs in the festival. An offshoot of City Ballet, the Miami company understands what Balanchine discovered and taught: how exactitude needn’t sacrifice warmth; how even in Romanticism, rhythmic accuracy allows momentum to build.”

You can see in her own words what each of these dance experts sees in Lourdes Lopez.

A Conversation with Lourdes Lopez

We spoke with Lourdes when she was in New York City for the Balanchine: The City Center Years festival at New York City Center in early November 2018.

You are American and Cuban, New York and Miami, ballerina, mother and artistic director. How does being a Latina inform this?

I think being Latina informs everything I do. I’m not saying that if you’re Irish-American, or Polish, or Russian, it won’t. I just feel that your culture and how you were raised, the aesthetics that you have, the philosophies that you have, inform any human being, or should I say, should inform any human being because it’s what makes us unique. It’s what makes us not different, but unique and interesting.

“It’s what makes us, not different, but unique and interesting.”

Everything I’ve done comes from this perspective of being Latina. Maybe that’s how I look at dance. Maybe that’s how I look at ballet. Maybe that’s how I look at dancers, how I look at works. I’ve never been anything else but this. My upbringing was one of tremendous pride. This was instilled in me, and the word is “instilled” because it has to be instilled in you. You are not born with it. It’s taught to you. My whole upbringing instilled me with a tremendous sense of pride for my culture, and for who I am.

It wasn’t that you’re different or you’re better. This is who you are. You should maintain it because it belongs to you. It doesn’t belong to everybody. You should be proud of it.

It was always there. We spoke Spanish at home. We didn’t speak English. We learned everything we could about our country Cuba. Yes it was under communist rule. We understood all that, but that’s not the main thing. We learned about the food, the music, the culture, the history, our poems, our heroes and our liberators.

I think it’s important for every human being to know where they came from, to have an understanding of that. When I would speak to Russian teachers of mine, they did the same thing. They would speak so beautifully of their mother country. My parents would always say, “Tiene la sangre,” (It’s in your blood). It’s true. You carry it inside of you. It’s who you are. It’s your DNA.

I grew up with a strong sense of self because I was Hispanic. I had a sense of belonging and a past. I had a history and a culture. I also grew up with a great sense of gratitude to the United States for allowing my parents, myself and my sisters to come to this country and be able to do what we wanted. Our hope for the future was here.

I grew up with a strong sense of self because I was Hispanic. I had a sense of belonging and a past. I had a history and a culture. I also grew up with a great sense of gratitude to the United States for allowing my parents, myself and my sisters to come to this country and be able to do what we wanted. Our hope for the future was here.

They embraced us. They opened their arms. My parents came with literally nothing, no money, zero. They were able to raise three daughters who contributed to society in one way or another, contributed to this country. So I grew up with this real sense of gratitude for being here in the United States and being able to do what I’ve become.

Then among all of this was an interesting sense from my parents of – follow your dream. We are not going to rein you into any kind of preconceived parameters of a culture or a gender at all. You would think that parents who came from Cuba in the 1960s would say no, this is your course and this is what most women do. They go on this track. I just didn’t and they allowed for this. I deviated from it and they allowed me to deviate.

At the age of 14 I moved to New York with my sister who was 19. When I think back to what my Cuban parents did in 1972. It was the worst, worst time in New York. There were hypodermic needles on the street. It was a black, dark period for New York City. It was not what it is now. For my parents to say, “Go, follow your dream. We’re going to support you.” Who does that? I couldn’t do that. I have two daughters. For them to go to college at 19 was heartbreaking for me.

Being Latina informed everything I do because it’s who I am. I can’t look at a ballet or a dancer without looking through Hispanic eyes, whatever that means. It’s wonderful to belong to something, to come from something, to know that it’s in you. That it distinguishes you in a special way, not that it separates you from other people. It just distinguishes you.

When you said ballerina/mother, New York/Miami, I think I had exceptional parents who didn’t respond like other parents in the 70s would have to an unusual wish that one of their daughters had, a desire, a talent. It might come from that whole immigrant philosophy of you are here for one reason which is to reach your potential. So you go for it.

“You are here for one reason which is to reach your potential. So you go for it.”

Where did that dream come from? Did you dance Hispanic dances growing up?

No. It was purely fate. I had problems with my legs. I was flat-footed. I had very weak muscles. I wore orthopedic shoes from the time I was five and a half until about eight. They were corrective shoes, boots.

Then the orthopedic doctor who was treating me said to my mother that she really needs some exercises, more than what she is doing in physical education in school. Something, gymnastics, ballet, just something to start to strengthen her legs. My mother being Hispanic said, “Gymnastics, no way.” We’re not having anybody tumbling and breaking their neck. We’re going to do something graceful. We’re going to do something feminine. We’re going to do something refined. So they put me into ballet.

I started doing this little Mommy and Me class at the age of five and a half where I would go once or twice a week. It was a little Cuban school in Miami. I didn’t really learn things. It was an academy. It was play basically. At the age of eight, my shoes came off and I remember when my Dad saying to me in the kitchen, “We can’t really afford the classes any more. Your boots are off, your legs are fine — unless you really want this.”

We’d only been in this country for seven years, and were very much living an immigrant experience, so my dancing was a sacrifice. I didn’t miss a beat. I said, “No, I love it.” So my mother moved me from that little ballet school to a Russian teacher named Alexander Nigodoff who was from the Bolshoi, and somehow ended up in Miami.

It was there that suddenly ballet became a thing, meaning that these steps had names and there was a right way and a wrong way to do them. There were ballets like “Sleeping Beauty,” “Swan Lake” and “Giselle.” They had stories and composers. I knew nothing about this. All of a sudden there was a world and a community that he opened up to me. Nijinsky and all these names and these ballets, this world he taught me about.

That’s really when I became hooked at the age of eight. I just became obsessed with this world. It was a world where you had to use your mind and your body, and it was heartfelt. It wasn’t just math where I’m just using my brain, which I was also very good at. I had to use my intelligence. I had to be a thinker and use my body. I loved being physical. It was also emotional. You could lose yourself in all of this.

So I did that for three years and then on a fluke, my father was working for an airline cargo service. He had to come up to New York and we decided to come visit for the first time as a family on standby tickets. My mom took me to a ballet school here, called the Joffrey Ballet, just for me to continue my classes. They offered me a scholarship on the spot. I remember my Mom came into the dressing room and said in Spanish, “Te andado una beca.” I said what’s a “beca.” I had no idea what that word in Spanish meant. I never heard it before.

I was ten and I think that at that moment my parents got a sense that I showed some type of promise for this thing that I liked doing. The next year they moved me again.

Isn’t it unusual for a Latina to make it into New York City Ballet?

Some people have this idea that ballet is elitist, but those steps, the movement is not elitist. They are what they are. It’s the institutions or the individuals that take it down that path. The only thing that’s unusual about a Latina being in the School of American Ballet is I didn’t have the financial opportunity. That’s what was given to me.

School of American Ballet gave me a scholarship. Did they give me a scholarship because I was Latina? Latina didn’t exist at that time anyway, I was Cuban. No, it’s because I showed some talent. The opportunity was given to this child in Miami, who unless she had the financial and human resources to get to New York, would not have been seen.

What the School of American Ballet or whoever was donating to the School of American Ballet at the time, and most of it was the Ford Foundation, they used those resources to go around the United States and look for talent. Actually Suki Schorer was one of those talent scouts as well. That’s what I’m talking about. When people say it’s this and that, no, no. It’s not about body type. It’s not about culture. It’s not about race. It’s not about color. It’s about opportunity.

It’s not about body type. It’s not about culture. It’s not about race. It’s not about color. It’s about opportunity.

Everything in life has specific parameters. If you want to be a basketball player, you can’t be 5 foot 4 inches tall. If you want to be a boxer, you can’t be tiny or weak. If you want to be a sprinter, you’ve got to be fast. If you want to be a marathon runner, you have to have endurance. Everything has something that you chose.

So ballet does require a specific body type, a specific dedication, a specific discipline, a specific focus, a specific passion. It requires that, but those things don’t only belong to one culture, or to one race, or to one color. I’m not saying there aren’t people out there who believe only one race should be dancing. I know that there are. But for me, it’s about talent. It’s about bringing that to the art form and understanding that it’s holding the art form up. If you’re right for it, you will get there.

With New York City Ballet, when I was training at the school, it was the old Russian classical training.

Are you Vaganova Technique?

No Vaganova came after Balanchine. When Balanchine came to the United States in the 1930s, there was very little ballet here. He brought the Imperial Theatre. It’s what he knew. It’s what we call old classical Russian training. It was a lot faster than even the Vaganova. Vaganova is very slow moving and has some wonderful aspects.

It was in his choreography that he took what he understood of classical ballet and moved it forward and Americanized it in terms of the rhythm, the speed, the clarity, the jazz. He added American jazz to it. All of that you learned once you got into the company. It was like I’m going to teach you algebra, calculus and all that. You’re going to do your experiments at the university, but here you’re going to learn what it is.

So we would get into the Company being able to do anything and everything asked of us. When you were in the Company dancing those ballets, you learned how to dance his way through his works. It’s changed a little bit now. They are trying to learn that at the school level. It’s like trying to do research in high school level without getting the high school learning in place first.

I don’t think it’s strange that a Latina was at the School of American Ballet. Did I walk into SAB in the 1970s and notice everybody else was blonde and blue eyed? Yes I did. Absolutely, because most Hispanics hadn’t been given the opportunity like I had. It was a fluke that I was even here with the Joffrey. I didn’t come here to dance. I just came to visit. The Joffrey offered me a scholarship which led my parents to go, “Oh my God. Maybe she does have something. Let’s figure it out.” I ended up at the School of American Ballet in New York and in New York City Ballet…

So yes, I’m one of the few Latinas in the history of New York City Ballet, but it’s only because I got the opportunity.

That’s New York.

It’s also America. It’s also the United States. It really is the land of opportunity. I wouldn’t have been able to do this anywhere else.

“It’s also America. It’s also the United States. It really is the land of opportunity. I wouldn’t have been able to do this anywhere else.”

It’s the Jerome Robbins Centennial. What was it like dancing for him?

It was great. My generation had both Balanchine and Robbins. Talk about the dichotomy of mother/ballerina, New York/Miami, Balanchine and Robbins were two geniuses of the art form in the same theater, with the same dancers, and they were as different as a cat and a dog.

It was like black and white. Balanchine was nurturing, loving, caring and respectful. He knew how to move his dancers seamlessly like this. There were some hiccups and things like that, but for the most part this was someone who had a tremendous amount of love and was really like a father figure. There was a real sense with Balanchine that if you didn’t get it today, you’ll get it tomorrow. If you didn’t get it tomorrow, eventually you’ll get it. And if you don’t get it, that’s okay.

“Balanchine was nurturing, loving, caring and respectful.”

After seeing his country blow up and experiencing so many hardships, I think Mr. B just put his trust in fate.

Jerry was very different. He was a taskmaster. He was demanding. He wanted to see it one way. Whereas Balanchine said, “Show me what you think about it, show me how you feel about it. What does Lourdes think about this variation?” Jerry was like, “This is how I want you to do it.” Talk about parameters. You had very strict borders to work with and you had to somehow find yourself within those borders.

Jerry was very different. He was a taskmaster. He was demanding. He wanted to see it one way.

But I learned a lot from Jerry. I learned about theater. I learned a lot about timing. I learned how you tell a story. I learned how to act on the stage. You have to become a character. I didn’t learn that from Balanchine, I learned that from Jerry. Before you enter the stage if you’re a character, backstage you have to be that character. You can’t only be it the moment you step on stage.

I learned nuance from Jerry, not from Balanchine, interestingly enough. How a step can have its own narrative. How that tiny little step can tell its own story. Jerry was an incredible teacher of the theater as a whole. He made you understand the lighting, the costume, the community in a work. For example in “West Side Story” or any of his ballets, everyone has to be a character or else it doesn’t work.

Jerry was also very nice to me. He could be difficult, but I always felt that if someone is going to be difficult, they better back it up with some talent and genius. Then I’ll take it. If I’m learning, I’ll take it because it’s only making me better. He backed it up with all of that.

It was an extraordinary time to be in one theater with those two men. There are very few of us left who were part of that.

When did you retire from New York City Ballet?

I don’t like to say that I retired. I like to say that I got tired. (Laughs). I stopped dancing in 1997.

What happened between then and 2012 when you moved to Miami City Ballet?

The intervening time is what really got me here. I wanted to be involved in the art that I knew and wanted to keep on giving back to dance if I could. I was totally comfortable stopping. I had danced so much, more than I ever thought I would. They say it’s a hard shift for a dancer, but I didn’t have a hard time at all. It might have been different things. I had already been married. I had a child at this point. I had gone to school a little bit already. By the time I stopped dancing, I had matured.

I was really comfortable and happy. I was healthy. My body didn’t hurt. I was dancing well. It was important for me to stop at height. Maybe that’s my Cuban pride, my own Latina pride, but whatever it was, it was important for me to stop on a good note. So the transition wasn’t difficult for me, it really wasn’t at all.

I think what was difficult was finding a community because dance is such a small wonderful little community where we all share the same history and sense of humor and struggles. So I did a whole bunch of things. I worked on television for two years which I didn’t like. It wasn’t an industry that spoke to me. I then started teaching at a school here in New York, Ballet Academy East. I started teaching all levels and that I loved. I felt like I was giving back to dance.

I did that for a couple of years and professionalized the school. I became their director of student placement and curriculum planning. I understood what to teach from the time you were six until the time you were eighteen and graduated. I dealt with parents. I dealt with students who didn’t want to dance, but wanted to do something else, or wanted to dance, but couldn’t. I dealt with all those things. I was on the business side as well which is great.

Then I was asked by Barbara Horgan, who was Mr. Balanchine’s personal assistant for many years, if I’d be interested in running the George Balanchine Foundation. I said yes, but I didn’t even know what it meant to be an Executive Director. I entered the organization and shadowed their present executive director for a summer, just to learn. That was an illuminating experience. I owe Barbara so much because that is where I learned about budgets. I learned how to write proposals. I understood this is what the project costs, this is what you have for it, this is what you have to raise. I understood board and governance, all those things you don’t think about as a dancer.

I learned a lot about Mr. Balanchine as a man, but even more as a choreographer. His full life and how he programmed, how he did things. All his history was there available to me. So I did that for four years.

Then I was asked by Christopher Wheeldon, the choreographer to start a ballet company.

Do you choreograph?

No, I have no interest. I listen to music and just hear the music. I don’t see any steps. So Chris said I’m interested in starting this small ballet company and he had some interesting ideas about what it could be like. He wanted to create a very collaborative environment with other artists from different disciplines. So we just packed up and went off to see what would happen.

Is Morphoses still going on?

It’s inactive. My hope was to continue Morphoses as an offshoot of Miami City Ballet because Miami City Ballet is a big company. It’s its own kind of beast, a traditional, conservative ballet company: a school, and rep, and theaters, and audience, and donor base and all of that. I thought wouldn’t it be interesting to have Morphoses as something, but while focusing on moving Miami City Ballet to the next level, I couldn’t really focus on Morphoses.

Along the way you founded the Cuban Artists Fund

I founded the Cuban Artists Fund with a great friend of mine, Ben Rodriguez-Cubeñas. He is a Cuban-American program officer for Rockefeller Brothers. He loves ballet so he would come to performances all the time. Ben had been to Cuba a couple of times. He said, I have this idea. I want to start a fund to help Cuban artists on the island and Cuban-American artists here. To help them financially, help them in terms of resources, help them in terms of networking. We met another friend of his, Maria Caso who was also involved in the visual art world here in New York.

The three of us got together over a bottle of wine. It was really Ben leading the way. Ben understood 501 (c)(3) not-for-profits, getting the filing and all that was his world. That was 1998. I think we’re about to celebrate our 20th Anniversary. Ben has been the powerhouse behind this. We would go to Cuba and take things, leotards, tights and shoes; paintbrushes, paint, film, batteries and cameras. We took little things for artists, even paper. It was so rewarding because they had so little. Every little thing that you took meant the world to them because they were able to create.

So now it has flourished and Ben has gotten involved in the artistic and cultural world in Cuba and here. We have exhibitions. When Cuban artists come to the United States, we offer them space and bring an audience in. It’s really quite wonderful.

Do your daughters dance?

My oldest Adriel, who is at Stanford Business School, never danced. She loves it, grew up backstage and in the classroom. She loves music, theater and dance. She knows it, but did not want to dance herself.

My youngest, Calliste who is 17 now, started dancing at Ballet Academy East here and was very, very good. But then we moved down to Miami and she discovered sports. She is captain of her Lacrosse team and on the swim team as well. So she left ballet long ago, but she comes all the time as well.

If there is one thing Latin, it is family. You accomplished a lot while raising a family. How does it all fit together?

I wish I could say, oh I had it all, but no you don’t. Everything in life takes sacrifice. Everything in life. I want freedom. I’m going to pack my family up and going to go to the United States even though I’m teaching at the military school and my entire wealth is in Cuba. It’s one of the things my parents taught me. Nothing is free in life. It all takes work and sacrifice. If you’re not willing to do that, you’re not going to get it.

It hasn’t been easy prioritizing. One day my family takes precedence over what I’m doing and other days, the work takes precedence. It’s a fluid situation. Have I been present as a mother as often as I wanted to? No. Have I been present as an artistic director? Honestly much more so than as a mom. But I managed to raise two really wonderful kids, and I have great relationships with them because they understood that I’m passionate about this, that I’m giving myself over to something. And they don’t always realize that until much later, when they become adults. They both now have their own passions too.

I also remember something that my mother used to say to me. She would say, “Children just have to know that you love them, that when they really need you, you’re going to be there.” And that I’ve done. It’s hard. I don’t want to lie and say it’s been a piece of cake. It’s hard, but I love both of the things I do. Having both worlds is really important to me.

As the only artist on the Ford Foundation Board, how are you trying to impact our society?

My position on the Ford Foundation Board of Trustees has impacted me deeply. Our community engagement efforts have grown and strengthened. You can find all of the programs, mainly geared towards school aged children and specifically those from what we call, Title One District schools. These are the schools that predominantly serve students from low income and poverty level communities.

While these are wonderful outreach programs, one of the ones I am most proud of and that I personally started, is our work with incarcerated women. We are working with a program here in South Florida called, Leap for Ladies. This is an 8-month program which helps incarcerated women re-enter society, by helping them with networking, teaching how to write resumes and interview, giving them the resources they need to be successful.

We did a small pilot program, where 8 graduates from the program were invited into Miami City Ballet, we showed them a small presentation of what we do, invited them to watch rehearsals, they met with dancers to discuss issues that we all face in our lives, regardless of our past, we did a short body language workshop and then I taught them the beginning of the ballet, Serenade, which is just the arms.

They also came to our Program 1, which was Concerto Barocco, Company B and Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto #2. After the holidays we plan on getting together to further develop the program. It was such a rewarding day for us, but also for the women. They felt honored and validated as human beings and that day, gave them a lot of hope for what their future might entail.

What drew you to Miami to take on this Artistic Director role?

It was organic. It was a ballet company. It was the Balanchine and Robbins repertory that I understood and grew up on. I am part of that legacy so I’m committed to it. The reason I said yes, was because it was Miami, because I was raised there. It felt organic. I speak the language. I know the culture. I was raised there. If it was Juneau, Alaska, I would have said no, but Miami is where I was raised, so it felt right.

What is coming for Miami City Ballet?

The dancers are fabulous. What I love about Miami City Ballet is a little bit how I felt growing up during my years at New York City Ballet. Even though in respect to cultures, there wasn’t that much diversity, there was diversity for me, the way that I looked at it in respect to looks, body types and looks on stage. I loved that. I respect, admire and can appreciate when the curtain goes up and they all look alike and they’re all lined up.

But it’s not necessarily what I want. I love curtain up and it’s oh my God, there are 32 different people out there. I have individuals as opposed to one clone. That’s what I love about the dancers at Miami City Ballet. When the curtain goes up they are all on the same path, same aesthetic, and same drive, but everybody comes from a different place. I think it’s what makes Miami City Ballet a special kind of community on stage. We’re all from different places, but we’re here in this little city together, making it happen ourselves.

“When the curtain goes up they are all on the same path, same aesthetic, and same drive, but everybody comes from a different place. I think it’s what makes Miami City Ballet a special kind of community on stage.”

I adore that. It brings a kind of vibe and a kind of humanity to the stage, a kind of community that you don’t always get in companies.

What’s next for Miami City Ballet? I feel weird because people always ask, “What’s your vision?” I don’t have a vision. I want to continue bringing the best to our dancers, bringing the best to our community, and making them better than they were. I want to have the world see the wonderful work we do. I love it when groups outside our community invite us to come and perform. It’s important to be able to share the gift we have as artists. That’s where I hope to keep growing.

Ballet is a classical art. What does it have to say to us today?

My motto is that great art is great art, whether it’s Beethoven, Mozart, Van Gogh, the Beatles, or ballet. If it’s great, it’s going to speak to audiences throughout the ages. My legacy is Balanchine and it’s important for me to make sure that Mr. B’s ballets and Robbins’ ballets are danced the way that they intended.

The word intent is really very important because ballet is a living art form. It’s not like a painting that just stays there, or a score that we all know. Ballet is effusive. It’s amorphous. The moment you complete that step, it disappears. We in the next generation have a responsibility to preserve the choreographer’s intent.

I think like any art form, it’s going to evolve based on the artists who contribute to it. Years ago I read about an article that came out during Mozart’s time in the 1700s. The author noted that when Mozart would play, the audience was older and worried that the audience was going to disappear.

I think it’s a concern that we always have. Mr. Balanchine used to say, “We’re selling ice in the winter. If we disappear, nobody cares. Nobody even wants it.” So I think artists always have this kind of insecurity that what they are doing, the art form they are involved in, is going to disappear.

I don’t believe that. I think it would have disappeared a long, long time ago. I think it’s going to change and morph into something else. It has to or else it’s really going to be like the dinosaurs. The same way that “Giselle” has survived along with “La Sylphide,” “Swan Lake” and “Coppélia.” The great ballets will continue and people will refresh them, preserve them, and maybe reimagine them. I think it’s up to the artists. There are going to be heroes who respond to the society around them.

“I think it’s up to the artists. There are going to be heroes who respond to the society around them.”

Do you see any of these artists on the horizon?

Yes of course. There’s Alexei Ratmansky. There’s Justin Peck. Christopher Wheeldon is one of them. Liam Scarlett is another.

They are out there. It’s a little bit like dancers. There are some that are like a garden that blossoms and it’s gorgeous, but then you never see it again. It withers. It’s short-lived, but boy while it lived it was great. Then there are others who are annual. Season after season those daffodils pop up and then go to sleep. Everybody is different.

Thank you. This conversation wasn’t just about ballet.

Nothing’s ever just about ballet.

“Nothing’s ever just about ballet.”

This is about who we are.

I’m in New York this weekend for the Balanchine Festival at New York City Center where you have companies practicing a classic art form that still has the power to bring different communities together.

The companies this weekend are from Russia, France, Great Britain, New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Miami. All have different aesthetics, different perceptions, philosophies, backgrounds, cultures and histories. We are about as different as we can possibly be, yet there we are in one theater, under one roof, sharing a stage equally and speaking only one common language, which is dance.

That’s all we speak, but because we speak that language, we treat each other with respect and generosity. It made me think this is what the art form is. This is ballet.

We come from different backgrounds, but in ballet, we are one. This is who we really are.

“We come from different backgrounds, but in ballet, we are one. This is who we really are.”

www.miamicityballet.org

www.fordfoundation.org

cubanartistsfund.org

balletacademyeast.com

www.balanchine.org

www.nycballet.com

www.sab.org